By VANESSA FRIEDMAN JUNE 23, 2015

The New York Times

When Jeb Bush finally did what he had been widely expected to do and formally announced his candidacy for president of the United States, his campaign came with all the accouterments of a contemporary political operation: new brand logo (a bright red “Jeb!”), website (Jeb2016.com) and multicultural pageantry.

But he was missing one thing: a shop.

Shop?

Hillary Rodham Clinton has one, listed on the top of her official website just after “The Four Fights” and “Organize.” So do Bernie Sanders, Ted Cruz and Rick Perry.

Marco Rubio opened his recently with the email blast: “It’s Here — Shop Now!” Rand Paul opened his the day he announced. Rick Santorum is planning to reopen shortly. Scott Walker’s store is “coming soon” according to his website, presumably when he makes his candidacy official.

“A campaign store is a very significant piece of a modern political campaign,” said Dale Emmons, president of the American Association of Political Consultants.

Not just because it enables voters to literally wear their support on their sleeves, or chests (though that is what both Democratic and Republican campaigns emphasize), and not just because it creates a reason for supporters to keep giving (you bought the T-shirt, but have you bought the sweats? How about a pair of flipflops?), but because of the data acquired.

Buy an item from a campaign store, and you are not actually purchasing a product; you are making a donation. According to Federal Election Commission regulations, candidates are not allowed to sell items for personal profit, so the product is the “premium” you get in return for your pledge.

As a result, when you put, say, a T-shirt or a coffee cup in your cart and go to checkout, you will, besides being asked for your full name, shipping address, phone and email, be met with the statement, “federal law requires us to collect the following information”: employer, occupation and whether you are retired. So far, so like any other online donation.

But when retail is involved, a little something extra is, too: personal preferences at a level beyond candidate.

The choice of a product can reveal whether you are a beer drinker, a sports fan or what cellphone you use. It can suggest that there are a lot of joggers headquartered in a specific region of the country, indicating that a campaign may want to direct its health communications to that state; or that you really, really, hate the other guy. It can reveal that you have a baby, or at least are close to someone who has a baby.

While the money is nice, the information is invaluable.

“It’s all about learning who your supporter base is,” said Marshal Cohen, chief industry analyst of the NPD Group and the author of “Why Customers Do What They Do.” “How do they live? What are their trigger points? What words resonate with them? It’s worth its weight in gold, in the political arena just like the consumer arena. We call it demographic profiling, because voter profiling sounds like a dirty word, but that’s what it is.”

A campaign designer who asked not to be named because he is currently employed by a candidate, but not authorized to speak for that campaign, said: “In a thoroughly modern campaign, customers in a shop will be segmented into very specific streams that will be organized into fund-raising buckets and targeted communications.” The segmentation, he said, “would track very closely to what exists in a large or midsize fashion chain.”

As a result, the more sophisticated the array of products, the more potential information can be gleaned, for those with the capacity (and staff power) to do so.

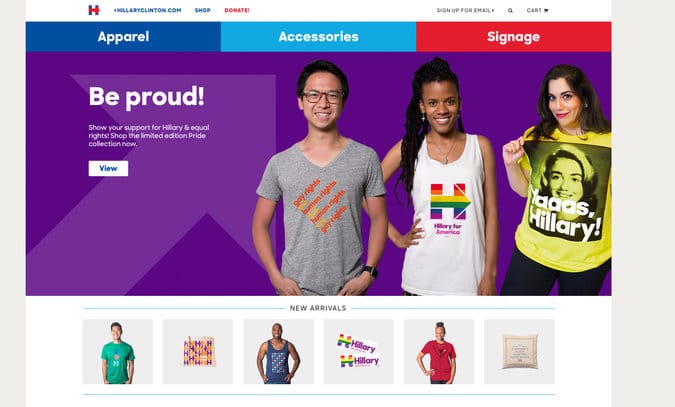

At the Hillary Clinton store, for example, the offerings go far beyond the usual T-shirts and baseball caps, to novelty items that wink at Mrs. Clinton’s own identity, like the best-selling Pantsuit T-shirt (a T-shirt with a jacket and pearls silk-screened on the front), a Future Voter onesie and the Canvass Canvas, a tote bag with the H logo printed all over the front, like so many Fendi Fs.

At the Rand Paul store, perhaps the most elaborate of all, there are approximately 100 items, including “fitted fashion” T-shirts, some with rhinestones, old-fashioned baseball script T-shirts, polo shirts and Steve Jobs-ian

mock turtlenecks, not to mention Rand-branded Beats headphone skins, skullcaps and an entire section devoted to anti-Clinton merchandise.

Steve Grubbs, the store manager, predicts that the store will expand to more than 200 products during the course of the campaign.

For candidates like Mr. Rubio, Mr. Perry and Mr. Sanders, who sell only a limited amount of merchandise — generally T-shirts, buttons, baseball caps and some stickers and signage — the psychographic possibilities are relatively limited. (There’s a tie pictured on Mr. Perry’s store but not offered for sale, so perhaps more inventive goods are coming.)

Still, the trend in campaign stores, even in the more basic emporia, is limited edition merchandise geared to specific events: LGBT pride, in the case of Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Sanders (think rainbow stripes); Father’s Day in the case of Mr. Paul. Such collections provide not only another reason to shop/donate, but also insight into what issue may be most important to a particular supporter.

“It’s a signal,” said Scott Galloway, the founder of the digital research firm L2 and a clinical professor of marketing at the New York University Stern School of Business. “I would say a faint signal, but definitely a signal.”

As are multiple purchases, which alert a campaign to someone who may be willing to become a local volunteer.

All of which accounts for the increasing willingness of campaigns to shoulder the burden of retail, not traditionally part of the required political skill set, and one that comes with its own set of challenges.

Sloganeering gear has been a part of campaigns for more than a century. (There is an Abraham Lincoln lantern from 1864 at the New-York Historical Society, as well as a Theodore Roosevelt bandanna from 1912, among other memorabilia.) But it was largely unregulated and uncontrolled. Vendors would show up at events and hawk their wares to boosters, with the candidates themselves having little or no control over the products or the images they portrayed.

Taking ownership of that was, said Joe Rospars, founder of Blue State Digital and mastermind of President Obama’s digital campaign in 2008 (among the first campaigns to identify and exploit the benefits of an e-commerce operation) and 2012, about having a “higher aspiration” when it came to political design, and a more thoughtful approach to branding.

“We made a very deliberate decision about it,” Mr. Rospars said. “We knew we had a brand that was different in 2007, and we had to approach it in a different way. In a world where you are relying on small donors for your margins, you have to press for every last advantage.”

The aforementioned anonymous campaign designer, who also worked on the Obama campaign, said that at that time the visual team was expected to come up with new proposals for products every week for different personality types: “What would your sister want to buy? Your mother? Your uncle?”

But it is not simple, from either a product point of view or an accounting one.

Because campaigns do not have the logistical capability to warehouse hundreds or thousands of products, they generally buy inventory, made according to their own designs, from manufacturers and then subcontract third-party vendors to handle the fulfillment — i.e., taking orders and shipping products (and dealing with the occasional return).

In 2008, for example, the Obama campaign worked with Tigereye Design — an Ohio-based company that describes itself as “union shop specializing in promotional products for Unions, Democratic, Progressive and Charitable campaigns” — to handle their logistics, as well as to produce much, though not all, of the merchandise.

The Rick Perry campaign is working with primesigns.com, which also bills itself as a “union shop,” and the Rand Paul campaign store is run by Mr. Grubbs who happens to be Mr. Paul’s chief strategist for Iowa as well as the founder of Victory Enterprises, a company that specializes in online design-your-own products and has a variety of e-commerce sites.

Then there’s the issue of supply and demand, which can be complicated by the need to keep products made in the United States. (If a candidate is running on a jobs platform, it may be hard to justify buying products overseas.) The Santorum campaign, for example, has decided not to stock Mr. Santorum’s famous sweater vests this race, though they offered them in 2012.

The problem, according to John Brabender, Mr. Santorum’s top strategist, arose during the last campaign when they could find only one American manufacturer and ended up with so many back orders that they were concerned about creating disgruntled, rather than enthusiastic, purchasers (or rather, donors).

But while the majority of campaign stores trumpet their 100 percent American-made products (none as loudly as Mr. Rubio, whose store tag line is “A New American Store”), there are exceptions: some of Mr. Paul’s products, while they are acquired from distributors in the United States, are made overseas, according to Mr. Grubbs.

“Almost all cellphone cases are made in Asia,” he said. Mr. Paul’s website sells eight different cases, including models for the iPhone 5 and 6, and the Samsung Galaxy 4 and S5.

“Our goal is to have 100 percent of our products produced or printed in the United States,” Mr. Grubbs said. “But we believe people should have the option to purchase a wide variety of items, and will continue to provide a variety of products that let people take their brand support with them however they choose.”

The design of each store itself, as well as the products, is handled by the respective campaign. Indeed, the ability to shape a personality and tone is part of the attraction of a campaign store, just as it is for any brand.

Hence the Clinton campaign’s decision to photograph its products on volunteers of all genders, ages and ethnicities, as opposed to simply displaying them on a plain background; and hence the Paul campaign’s choice to showcase its products largely on groups of millennials. The “models” serve as subliminal messaging tools for different demographics.

Yet at the same time, the more complicated the retail approach, with all its potential upside, the greater the risk.

Not so much because of the commercialization involved — the selling, literally, of the presidency — which all campaigns claim has not produced any blowback thus far, but because as products push the boundaries of humor and competition, they begin to flirt with the possibility of offense.

“Are we reaching the point where we have to ask the question, ‘What will be the first merchandise gaffe that chews up a news cycle?’ ” Mr. Rospars asked.

“Probably.”

There are more than 500 days, and hundreds of products, to go until Election Day. As for Mr. Bush, his campaign says his gear will soon be among them.

A version of this article appears in print on June 25, 2015, on page D1 of the New York edition with the

headline: Happy Days Are Here for Swag .

© 2015 The New York Times Company